Mapping the American Economy’s Internal Lines of Fragility

This is the second essay in Stress Test, a series on how major economies will absorb tariff shocks through structure, not politics.

This essay focuses on the core design of the American economy, the deeper machinery and constraints across its layers, that enable or limit its capability to adapt to tariff shocks.

In theory, the U.S. has multiple options. But the real question is: How many of them can still work under stress?

The Architecture We Inherited

The modern U.S. economic model was designed for openness. By the 1980s, Washington had embraced a system defined by open markets, global supply chains, and financial liberalization. The idea was simple: a free-flowing world economy would not just maximize efficiency—it would reinforce American values and influence globally through economic systems.

That bet paid off handsomely for decades. America became the epicenter of technological innovation, capital formation, and consumption. The dollar became the world’s reserve currency. Risk was spread across borders, and the system itself appeared self-reinforcing.

But what we optimized for—fluid movement of capital, goods, and data—isn’t the environment we’re entering now.

Trade frictions, geopolitical fault lines, and inflationary pressures require a different kind of resilience. Not agility alone, but shock-absorption.

And in 2025, the U.S. economy’s ability to absorb shocks is constrained on multiple fronts:

Red Line #1: Fiscal Room Has Narrowed

In the wake of multiple crises—wars, bailouts, pandemics—the federal balance sheet has ballooned. U.S. public debt now sits above 120% of GDP. Interest payments alone are projected to exceed $1 trillion by 2026, consuming more than the entire defense budget.

This matters because fiscal space is the first line of defense in a trade war. You need resources to protect vulnerable industries, invest in new capacity, and soften the blow for workers. But today, almost every new dollar spent is financed—not from surpluses or savings—but through borrowing.

And that borrowing has started to come with a cost. After years of ultra-low interest rates, investors are demanding higher interest payments or yields on U.S. debt. That makes new spending expensive to justify, even when it's urgent.

Entitlements, which have to be paid by the government, are approaching their own cliff. By the 2030s, both Social Security and Medicare face depletion of their trust funds. These aren't small line items—they represent about half of federal non-interest spending.

So, we’re left with a shrinking pool of discretionary spending, rising structural obligations, and the fastest-growing line item being interest on past borrowing.

In short: the fiscal shock absorbers are wearing out.

Red Line #2: The Fed’s Narrow Path

Over decades, monetary policy played the role of national shock absorber. When growth faltered or crises hit, the Fed stepped in—cutting rates, injecting liquidity, and backstopping markets.

But the environment in 2025 looks different. Inflation is no longer dormant. Interest rates have been raised to over 5% to contain price pressures, and the Fed’s balance sheet remains bloated from years of quantitative easing (ex. Covid relief).

Essentially, the Fed’s hands are tied - it’s like a firefighter with only a small bucket of water left.

Trade war tariffs are pushing up prices for things like groceries and clothes. If the Fed raises interest rates to slow these price hikes, it could make loans so expensive that businesses cut jobs and the economy stalls. But if it does nothing, prices might keep soaring, making life even harder for everyone.

This is a no-win situation: the Fed’s usual fixes, like lowering rates, used to calm things down, but now they might make the economy shakier. Our economy depends a lot on Wall Street—stocks and investments—and those markets can panic faster than the Fed can act, causing bigger problems.

The Fed can still act. But the margin for error has narrowed dramatically.

Red Line #3: The Over-Financialized Economy

One of the most critical vulnerabilities in the U.S. system is that it is deeply financialized. Unlike bank-led systems in Europe or East Asia, the U.S. runs on market finance—venture capital, private equity, credit markets, and equities- rather than by producing goods, creating jobs, or raising wages. That system can scale quickly and allocate capital efficiently—but it is also prone to valuation bubbles, mispricing, and abrupt reversals.

Since the 1980s, the U.S.—like many advanced economies—has seen a growing share of economic activity and corporate profits concentrated in the financial sector, while the relative size of manufacturing and other “real economy” sectors has declined.

The broader financial sector (FIRE) now accounts for over 20% of U.S. GDP, nearly double the share of manufacturing (~10%). And by the early 2000s, it made up roughly 40% of all corporate profits.

Even equity markets, often seen as a proxy for U.S. dynamism, are distorted. Over 25% of the S&P 500 market value is now concentrated in just the top-5 tech stocks—firms with global supply chains, foreign revenue exposure, and regulatory sensitivity. They are market leaders; but they also become volatility multipliers.

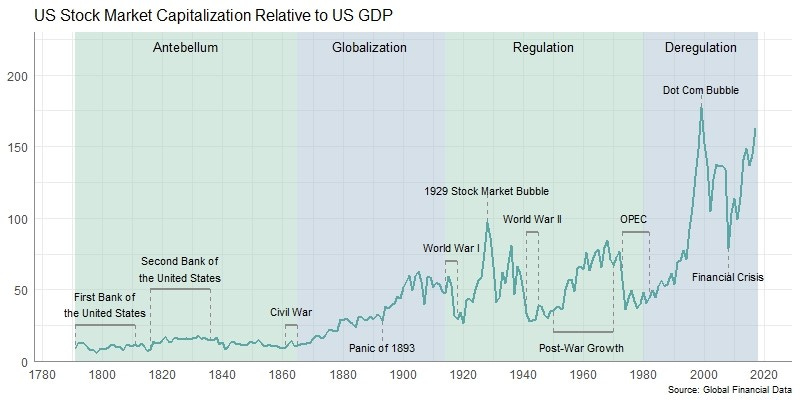

The ratio of the U.S. stock market’s total value to GDP—often called the “Buffett Indicator”— has dramatically increased over time, from 100% in the 2005-era to 200% in 2024 — showing that capital markets far outpace the aggregate economy.

Corporate debt is now higher than ever. Many companies used years of low interest rates to borrow cheaply and spend on things like stock buybacks, dividends, or buying other companies. But as interest rates rise, it’s getting harder—and riskier—for them to repay or refinance that debt, especially for those with lower credit ratings.

Furthermore, the venture ecosystem, while a driver of innovation, is structurally vulnerable too. Many startups remain unprofitable and rely on continuous capital inflows. Any sustained tightening—triggered by tariffs, inflation, or financial shocks—could ignite widespread retrenchment, particularly in tech and biotech.

Finance is no longer just an enabler of the real economy; it has become the engine itself. Hence, when the markets flinch, the whole system feels it.

Red Line #4: Industrial Depth Trails Strategy

After decades of offshoring, U.S. manufacturing has thinned. It now makes up just 11% of GDP and employs fewer workers than it did in 2000—down from 17 million to just over 12 million by 2020.

Whole industries—textiles, electronics assembly, furniture—migrated abroad following China’s entry into the WTO. The trade deficit in goods ballooned, and the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the consequences: critical shortages in everything from semiconductors to PPE.

Meanwhile, cost and complexity remain barriers: U.S. labor costs outpace Asia or Mexico, and while automation helps in high-end sectors, mid-tier manufacturing remains hard to re-domesticate without significant subsidies or steep price increases. That creates both economic and political tension: Americans support reshoring—until it raises consumer costs.

And even now, many firms hedge. They accept subsidies for domestic investment while keeping or expanding overseas operations.

The reality is this: you can’t rebuild industrial capacity overnight. It’s not just about capital—it’s about workforce, permitting, supply chains, and time.

Red Line #5: Tech as a Strategic Double-Edged Sword

America’s most valuable companies are also its most global. Big Tech—now a quarter of U.S. equity value—is deeply embedded in global supply chains, and dependent on Chinese assembly, Taiwanese chips, European markets, and growth from Asian cross-border data flows.

This makes tech both a strength and a vulnerability. Tariffs, export controls, and capital restrictions can reverberate across their business models. Chips, cloud infrastructure, and device components all rely on interdependent global ecosystems.

Even when aiming to “decouple,” firms often find themselves caught in the middle. Compliance costs rise, market access is threatened, and innovation timelines stretch.

In short: The crown jewels enabling global influence are also our most exposed assets.

Red Line #6: Dollar Dominance—Still Real, But Less Absolute

The dollar remains the backbone of global finance. It facilitates over 80% of global trade finance and makes up 55% of foreign exchange reserves. This gives the U.S. unmatched economic leverage: it can sanction, incentivize, or stabilize at scale.

But that leverage is increasingly being used in explicit strategic ways—weaponizing access to the dollar system for trade, sanctions, or security goals. While effective in the short term, these moves have triggered gradual hedging from other economies.

We're seeing more trade settled in local currencies, rising interest in alternatives like the euro, yuan, or even commodity-linked instruments, and regional payment systems emerging outside the dollar’s reach.

In a world of rising multipolarity, dollar privilege becomes a little less absolute.

The dollar is not being replaced. But the monopoly is slowly eroding. And with that, so does the automatic global appetite for U.S. assets—Treasuries, tech stocks, and real estate.

Red Line #7: Institutional Friction and Policy Paralysis

Resilience isn’t just about money or markets. It’s also about institutions—how quickly a government can respond, how coherently agencies coordinate, and whether long-term plans survive short-term politics.

On this front, America is showing strain. Institutional trust is near historic lows. Policy often swings with each electoral cycle. Major initiatives face legal challenges, budget cuts, or fragmented implementation across federal and state levels.

This makes long-range industrial or trade strategy difficult to execute at scale. Allies and competitors alike notice the inconsistency. And firms—domestic and foreign—adjust their bets accordingly.

A strategy is only as strong as the system that executes it.

A Macro Picture on Financialized vs Real Growth

Over the past four decades, the U.S. economy has come to lean ever more heavily on its financial sector, often at the expense of factories and real‑world production.

In 2000, financial services accounted for roughly 7 percent of GDP; by 2023, that share had climbed to 8.5 percent, even as manufacturing’s slice fell from about 12 percent to 10 percent—shifting $400 billion of economic weight away from “making things” and into trading paper.

Meanwhile, decades of rising stock buy‑backs and consolidation have buoyed headline growth but failed to lift living standards for most Americans. The top 1 percent of earners now harvest 20 percent of national income—up from 13 percent in 1980—and hold 32 percent of household wealth, while the median real wage for production and non-supervisory workers has inched up just 36 percent since 1979 even as GDP more than tripled.

As asset prices inflated, many regions—once industrial powerhouses—saw population declines (Rust Belt states grew only 2 percent in 2010–2020 versus 12 percent in the Sunbelt ), and firms lament persistent skill gaps even amid roughly 600,000 manufacturing job openings.

The result is an economy that “grows” on paper but leaves too many behind—a dynamic that breeds both economic and political disillusionment.

Where Industrial Policy Fits—and Why It’s Contested

Reintroducing industrial policy into a famously market‑driven economy is a historic turn—and a lightning rod for debate. On one side stand free‑market proponents, who argue that government “picking winners” distorts competition and crowds out private investment. On the other sit advocates for strategic intervention, who point to China’s decade‑long plan—“Made in China 2025”—and its rapid mobilization of factories in crises as proof that targeted subsidies and planning can rebuild capacity at speed. The U.S. CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 embodies this new approach: $52 billion in subsidies has already lured companies like Intel, TSMC, and Samsung to commit over $300 billion in new fabs and the promise of some 50,000 jobs . Yet industry voices remain mixed. Semiconductor analyst Malcolm Penn calls the legislation “only subsidizing the players already at the top,” arguing that long lead times and regulatory hurdles have slowed actual output increases . President Trump’s recent call to repeal the Act—citing ineffective spending and urging instead that “threats of new tariffs” alone can drive on‑shore investment—underscores the philosophical divide . In practice, dozens of CHIPS‑funded projects are still in the permitting stage, and some firms continue to maintain substantial Asian footprints despite U.S. incentives. The key test now is whether these policies can strike the right balance—marrying market discipline with strategic vision—so that “Made in America” becomes more than a slogan, and instead underpins the next chapter of durable, shared prosperity.

So What’s Holding—And What Isn’t?

The American economy still has deep strengths. It is innovative, flexible, and home to the deepest capital markets on Earth. The U.S. consumer remains a powerful force. The dollar still underwrites the global financial system.

But when trade conflict hits, what matters is not just strength—it’s slack.

And the slack has thinned.

Fiscal policy is more constrained. Monetary tools are more blunt. Financial markets are more volatile. Industrial rebuilding is underway, but far from complete. The dollar system is intact—but under question.

What we’re facing is not collapse. It’s constraint. A growing number of hard limits, built up over time, now intersecting in a more volatile global context.

And that constraint makes each future shock—tariff or otherwise—more consequential.

Looking Ahead

🧭 This is the second essay in Stress Test, a series on how major economies will absorb tariff shocks through structure, not politics. Each essay builds on the last to decode what’s really shaping global power. The next essay will explore the structure of China’s system.

I research and write these solo—if it brought clarity, do subscribe on Substack & X to support the work!

Thank you for sharing your well researched and objective analysis. It is very valuable to build understanding of the foundations and functioning of the world we live in today 🙏🏼🌎!

Great content and insight.

I wrote another perspective on it... https://benharrington1.substack.com/p/15-years-too-late?r=yp9ay